A tiny miracle: Powhatan infant gets a new heart

Bryson Slate looked like a healthy baby, but doctors quickly discovered he has a life-threatening condition.

For Chuck and Amanda Slate, watching their infant being taken in for a heart transplant was all the harder because he looked fine.

“It was really emotional,” Amanda said. “Here we have a baby who seems pretty normal on the outside but he has this huge life-threatening condition and we’re handing him over to swap out hearts.”

“It made it almost harder to hand him over because he seemed okay,” Chuck added.

Bryson Slate was only 4 months old when he became one of the 1,895 children in America to receive an organ transplant in 2018. He’s one of the many success stories being celebrated during National Pediatric Transplant Week, but the statistics belie the difficult road behind even the best outcomes.

Early indications

Bryson was born July 21, “a last-ditch effort” for a second child. Amanda and Chuck’s older son, then-7-year-old Landon, had always wanted another sibling and the couple had been trying for a while without success.

“I babysat so Landon had always been around infants and children and he was so nurturing,” Amanda said. “You could tell he was going to be a great big brother.”

Everything seemed fine for a while – the pregnancy and birth were normal and Bryson’s initial report at birth was good.

“His heart looked really bad even though you couldn’t tell from looking at him.”

The first indication that something was wrong came later that evening when the nurse listened to his heart and thought he had a murmur. That isn’t unusual in newborns, though, and it often resolves itself. But his blood sugar and temperature were also low. None of it was a major cause for concern, although it kept Bryson in the NICU for a week while doctors waited for it to clear up.

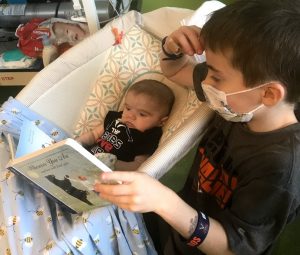

Bryson with his big brother, Landon.

“When they came back though, the doctor said his heart looked really bad even though you couldn’t tell from looking at him,” Amanda said.

Within a few hours, Bryson was in an ambulance being transferred to a more specialized children’s hospital.

Waiting

Bryson underwent a battery of genetic tests while doctors tried to pinpoint the problem. The Slates were told it would be a few months before results came in and they returned to their home in Powhatan to wait.

What doctors did know already was that one of Bryson’s problems was hypertrophic cardiomyopathy — his heart walls were so thick that it couldn’t pump properly.

While he still looked okay, the strain on his heart was impacting everything else, including his ability to breathe and eat. Bryson was evaluated at two hospitals before the parents contacted the University of Virginia Children’s Hospital Heart Center, looking for an earlier appointment.

“The condition of his heart was probably the worst they’ve ever seen.”

Within a few days, they had an appointment and the Slates headed out to Charlottesville.

They were about to spend a lot of time there.

Chuck at the bedside of his youngest son, Bryson.

“They said the condition of his heart was probably the worst they’ve ever seen in an infant with cardiomyopathy,” Chuck said. They said he’s going to need a heart transplant but he could go home on medication.”

A few weeks after that, the genetic tests came back and Bryson was diagnosed with Noonan syndrome, a genetic condition that can range from mild to life-threatening and that can lead to a variety of developmental problems, including heart defects.

Bryson was back at home but at 3 months old, he wasn’t gaining weight like he should. He was readmitted to UVA to get a feeding tube because the strain on his heart was making it too hard for him to drink milk.

“They knew that getting him bigger would help give him strength going into surgery,” Amanda said. “It also meant he got 1A status – the highest priority for a transplant.”

From skeptic to advocate

The thing was, Amanda said, she wasn’t a registered organ donor herself.

“I was one of these people, I’m ashamed to say, that had these misconceptions about organ donation,” she said. “I guess I’d heard as a child that the doctors won’t work as hard to save your life if you’re an organ donor. And I thought you had to go to DMV.”

“If I never do anything else in my lifetime, I’ve done this. I’ve done something good.”

While sitting with relatives all reeling from the news about Bryson’s feeding tube and impending transplant, one family member said they were going to go online “right now” to register as a donor.

Amanda hold her son Bryson, who received a heart transplant at only 4 months old.

“I said ‘what? That’s all you have to do?’” Amanda said. “I had thought you had to go down to DMV and stand in line. After Bryson’s diagnosis, I’d meant to go, but I just hadn’t gotten there. I don’t know why I hadn’t thought you could just do it online.”

Signing up right then and there “almost gave me a sense of peace and purpose,” she said. “If I never do anything else in my lifetime, I’ve done this. I’ve done something good.”

The call

From that point on, it was just waiting. Three weeks later, on Nov. 24, 2018, the call came. Bryson was only 4 months old.

The surgery itself doesn’t take long, Chuck said, but it was about 12 hours from the time they prepped Bryson until they were done. “They opened him up and started bypass before the new heart even landed,” he said. “Then as soon as they got the call that the heart had landed, they start getting ready to take his out.”

Everything was fine at first but at the last update, there was something wrong.

Tiny miracle. Bryson Slate is among the youngest heart recipients in Virginia.

“Bryson’s new heart wasn’t pumping like it should,” Amanda recalled.

He was kept on an ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation), which is a heart and lung life support system. The doctors believed that his heart might start pumping a little and they could wean him off the machine slowly over time as the heart picked up steam. The Slates signed transplant orders again, hoping ECMO could keep their son going until a new heart was found.

The next day, Chuck went in to see his son – Amanda said she couldn’t bring herself to look so she waited in the lobby with family. They were told to celebrate any tiny improvement in the situation and that success would be measured in small increments from here on out.

But when Chuck came out of the room, everything was different.

“Bryson’s heart just started up like a champion,” Chuck said. “That wasn’t what anyone had expected at all. They said they don’t use the term a lot, but they called it a miracle.”

Bryson was doing well but there was still a long road ahead. It was two more days before they were confident enough to even close his chest and the normal two or three-week recovery period turned into months.

“Bryson’s heart just started up like a champion.”

“He had a bad reaction to some of the medications and his kidneys shut down,” Chuck said. “They put in chest tubes and a breathing tube and he went on dialysis. During that whole time, he was unable to eat any food and it was Dec. 18 or 19 before he was ready to leave the NICU PICU to go to a regular unit.”

Back home

Chuck and Amanda had essentially moved to Charlottesville when Bryson was admitted on Nov. 1 and grandparents moved into the Slate’s home to take care of Landon.

“He was a rock star but he definitely started to break down after a while,” Chuck said. “One night we called and he broke down crying and then the next night, it was the same thing.”

Big brother Landon reads to Bryson in the hospital.

Landon wanted to be closer to his parents and baby brother so Chuck’s parents moved him into their home in Fluvanna, closer to UVA. From there it was only a 30-minute ride to the hospital so he got to see his family more often, but it was a much further commute to school.

Chuck’s father made the trip back and forth every day with his grandson.

In the meantime, Bryson improved slowly. His kidneys began to function again and by the end of December, he was released from the hospital, provided the family stay close by in Charlottesville.

Being out of the hospital presented its own challenges, Amanda said. Bryson was still on 13 different medications. “When you get home, you have to coordinate all of them,” she said.

“Nurses manage that with several patients at a time. It was all we could do to keep up with one.”

The Slate family. Party of four.

Adjusting to normal

At 8 months old, Bryson is down to only three medications and is doing well, although he has profound hearing loss – another result of Noonan syndrome.

Landon too, is adjusting to life with his parents back at home, along with a baby brother he’d spent little time with during the last 8 months.

“I think Landon thinks he’s one of the parents,” Amanda said. “The other day Bryson was crying and I called in for him to wait a minute and then he just stopped – I came in and Landon had picked him up and was dancing with him. He said ‘see, Mom? This is all you have to do.’ The two of them just melt each other; you can see it in the way they look at each other.”

“We pray for that donor family every day.”

As for the donor family, the Slates said they wish to thank them for their son’s life.

“We pray for that donor family every day, that their struggle becomes less and less,” Amanda said. “We can’t wait to talk to them.”

Organ, eye and tissue donation saves and heals countless lives. Register to become a donor today.