Cornea transplant lifts librarian from depression

Mary Jackson didn’t just get new eyes – she got a whole new way of looking at life after a double cornea transplant 25 years ago cured her not only of blindness, but of suicidal depression.

Now pushing 80, she’s more active than she’s ever been and grateful for her second shot at life.

Mary J. Jackson

Going dark

Mary was not yet 40 when she started having eye trouble in the 1970s. While working as a librarian at Thomas Jefferson High School in Richmond, she started experiencing double vision and problems reading as print looked blurry.

“I didn’t know how serious it was.”

“I didn’t know the severity of what was happening,” she said. “They told me it was allergic conjunctivitis, which is just pink eye, plus atopic dermatitis. I didn’t know how serious it was.”

The two conditions combined to leave Mary with untreatable failing vision and a huge problem for her career and lifestyle.

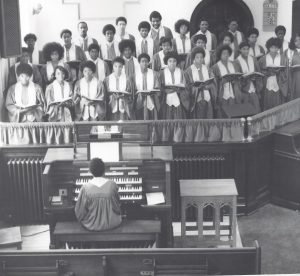

“There I was as a librarian with a problem of this magnitude. I was also in the music ministry at my church so I had to be able to read the music and I was getting my master’s degree. And all of that while I’m going blind,” she said.

Mary was in the music ministry at her church when she started to go blind.

Even with rapidly failing vision, Mary earned a master’s degree from the University of Richmond in 15 months. But that was the high point. Four years later, in 1980, her vision had become too poor to continue working and she was forced to retire from her 22-year career as a librarian.

“I was only 42 and I couldn’t work,” she said. “When school would start I’d really get depressed because I couldn’t go to work. I became suicidal and I’d have these pity parties every single day. No one was invited but my depression and my poor vision.”

Mary could still see a little – she could drive during the day as long as she knew the route well – but her vision continued to decline. She developed cataracts and her corneas became scarred. By the early 1990s, she could only drive to church and to Regency Mall – the only two places both close and familiar enough to navigate.

“I became suicidal and I’d have these pity parties every single day. No one was invited but my depression and my poor vision.”

Risking it

At church, Mary continued her work in the music ministry, memorizing the notes when she could no longer read them on the page. The pieces she couldn’t memorize, she rewrote “really really big” so she could see them.

But it was the depression, not her eyesight, that was the bigger problem. So when her doctor told her she could gamble on a cornea transplant, she decided to take a chance.

Mary playing the organ at her church.

“It was risky,” she said. “I could still see a little and the operation could have left me completely blind but I was going blind anyway. I figured blindness was going to be blindness so why not take a chance.”

The surgery was scheduled for Jan. 15, 1993 so Mary was completely unprepared when she arrived home in the evening to find a voice mail from the doctor saying a cornea was ready for her and the surgery had to be done the very next day.

The chances of success were only 30 percent and Mary wasn’t ready but she went.

Signing up

As she prepared for the surgery, she realized for the first time that she was being given someone else’s cornea – a gift of sight from a stranger who had signed an organ donation card.

“I hadn’t been for or against being an organ donor. I didn’t know anything about it,” she said.

But before she went in for surgery, she signed her own organ donor card.

“When the doctor took the bandages from my eyes the next morning, it was like a new world.”

A new world

Mary directing a music conference.

There was only a 30 percent chance the transplant would work — but it worked.

“When the doctor took the bandages from my eyes the next morning, it was like a new world,” she said. “The first thing I could see was the elation on his face because of the job he had done.”

Less than a year later, she had the same surgery again, this time on her right eye.

Now entering the 25th year since her first new eye, Mary said she’s discovered a bigger world than the one she left.

“I was taken out of the classroom but I was placed in a much wider arena than the classroom could ever hold,” she said.

Mary at an American Baptist Women’s Ministries luncheon in Melbourne, Australia.

She hit the road, traveling around the country and even to Australia with the American Baptist Women’s Ministries. She also began giving back to the donation community, talking to people who were candidates for cornea transplants and helping them through their fear.

“It became a passion of mine to talk to people who were candidates,” she said. “I talk to them on the phone or over email but when I was on the way to Australia I had to stop in Los Angeles and I got to have dinner with a woman I’d been communicating with over the phone.”

A medical miracle

“I call transplantation a ‘medical miracle,’” Mary said. “I don’t have 20/20 vision but I don’t need to have 20/20 vision – I can read and I don’t take reading for granted. It’s a privilege.”

For a career librarian, being able to read again is everything.

Mary, a career librarian, can read again.

But it’s not all she’s doing, even as her 80th birthday approaches.

“I’m on the board of the Old Dominion Eye Foundation and I’m the chair of Christian education at church and I teach Sunday school and I’m one of the editors of the church newsletter and I’m on several committees at church,” she said.

She also found time to pose for calendars – one for Donate Life Virginia and one for the National Minority Organ Tissue Transplant Education Program.

“I always say I’m a pin-up girl,” she said, laughing. She also says she’s been blessed with a second chance.

“Suicide didn’t work because there was an opportunity waiting for me,” she said. “It always makes me think of the line in the hymn – twas blind but now I see.”

Mary as a “pin up” calendar girl for Donate Life Virginia.