A Mother’s Journey to Discover Her Infant Son’s Legacy

At 12 weeks into her pregnancy, Sarah Gray received devastating news. One of her identical twin sons would be born with anencephaly, a fatal defect that affects brain development.

The shock ripped through her and her husband, not lessened by the fact that an in utero death of the sick twin could endanger the life of the healthy one. Certain factors in the placement of the babies meant that a selective termination would be too risky. All Sarah could do was wait and hope for the best.

Staying hopeful wasn’t an easy thing to do—particularly when the optimal outcome still involves the death of one child. But Sarah knew that a high-risk pregnancy like hers meant that she should do whatever she could to stay calm, stay focused, and keep moving forward.

The Grays 2016

After a particularly frustrating doctor visit, in which Sarah and her husband were unable to get the answers they desperately wanted to know about their child’s birth defect, Sarah wondered if there was a way she could help shed light on anencephaly somehow. His body would be too tiny to be a good candidate for donating for organ transplant, Washington Regional Transplant Community told her.

But was that really the only option?

What if Thomas (the ailing twin) would be able to assist, in a way, other people recover from this and other diseases through aiding scientists in their research? What if his tissue was donated to science?

His body would be too tiny to be a good candidate for donating for organ transplant.

Sarah’s mother worked in healthcare, and seemed to remember an instance in which the tissue of an infant with anencephaly was able to be donated for scientific study. Once she wrapped her mind around the idea, she felt herself relax. Doing the research helped her feel centered, and learning what she could about donation quickly became her focus.

This, she says now as she looks back, isn’t the end of Thomas’s story, but the beginning.

The next chapter

The twins were born with the best possible outcome—Callum was healthy. Thomas passed away six days later, and the donation process began and ended. Sarah and her family focused on caring for their new addition, but Sarah still wondered about the donation.

Sarah wanted to know more about the specific research Thomas’s gift was contributing to. She wanted to feel more connected to his legacy, to what he had been able to do—and maybe still was doing—in his own way. After all, what does it really mean when you donate a body to research?

She decided to look into it.

Inquiries to the transplant center that had organized Thomas’s donation of liver tissue, eyes, and cord blood only scratched the surface. Sarah was able to find out which institutions had received which gifts, but not which studies they were being used for. Surely, she thought, somebody would be willing to tell me more.

Finding Thomas

It was an ordinary day at Old Dominion Eye Foundation when an unusual email popped up in Associate Director Chrissy Jenkins’s inbox. A donor mom wanted to know what had happened with her infant son’s eyes.

ODEF is a leading center for recovering corneas and other donated eye tissue for research into diseases that affect vision. Once recovered, ODEF conducts some research in-house, while providing valuable resource to major research centers, as was the case with Thomas Gray. But families of donors tend to believe their loved one’s story stops at the recovering organization.

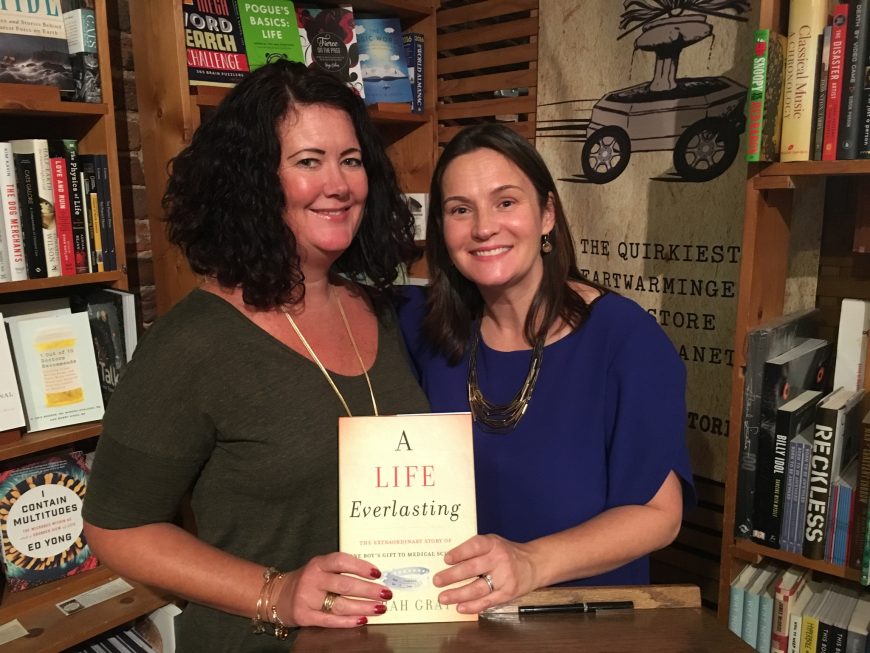

Sarah Gray with ODEF’s Chrissy Jenkins and Jennifer Payton

As Chrissy discovered that day in 2012, Sarah wasn’t content to let that be the case.

When Chrissy told Sarah that Thomas’s corneas had gone to Schepens Eye Research Institute at Harvard, Sarah jokingly replied that she was thrilled to be able to think of Thomas as getting accepted to Harvard. The graciousness of Sarah’s response caused Chrissy, a parent herself, to burst into tears.

A Short Life, a Lasting Legacy

On a business trip to Boston, Sarah found herself in close proximity to Harvard and decided to make a visit. Shortly thereafter—and two years after Thomas’s death—Sarah and her mother were on a tour of Schepens Eye Institute.

When Chrissy Jenkins initially heard that Sarah had visited Schepens, she worried it had been jarring for Sarah. She knew researchers were not trained to talk to a family member of a donor. It was so unprecedented. Had they been sensitive and compassionate? Had they given this donor the reverence she deserved?

Sarah assured her that her worries were completely unfounded. When they arrived, they quickly realized that the research staff were as curious about Sarah as she was about them. “It was almost like a blind date,” remembers Sarah, who broke the ice by asking all the questions that had been building up inside her for the past two years.

“I was in the presence of my son’s cells.”

Thomas’s corneas had been a valuable donation to a facility that requests only about ten pairs per year. “Infant corneas are like gold,” Sarah remembers being told, due to newborn tissue’s ability to regenerate quickly. It became clear the more they talked that Thomas’s corneas may actually be still in use in the lab—a corneal gift could go a long way towards helping research into cures and better treatments for blindness and eye disorders.

“I was in the presence of my son’s cells,” says Sarah. “I didn’t know how much I needed to hear that until I heard it. I feel such a sense of relief and peace and I feel like I just met his colleagues and coworkers and I’m proud of my son because he has a job.”

“I was in the presence of my son’s cells,” says Sarah. “I didn’t know how much I needed to hear that until I heard it. I feel such a sense of relief and peace and I feel like I just met his colleagues and coworkers and I’m proud of my son because he has a job.”

It didn’t take long for Sarah to start making other trips to other facilities—Duke, University of Pennsylvania, Cytonet in Durham, North Carolina, and Old Dominion Eye Foundation. At all but one, she was the first family member of a donor to make contact.

At each facility she visits, Sarah ends up establishing lasting relationships with the people who have made it possible for Thomas’s gift to benefit others. Those human interactions have helped her understand and celebrate her son’s short life, but long legacy.

And to Chrissy Jenkins and those others who facilitate the research, their job has taken on another level of satisfaction now that they’ve made contact with a donor’s family.

Opening the eyes of others to research donation’s rewards

Today, Sarah’s story has taken on a life of its own. With speaking engagements and now a book about her experience, she inspires and empowers others by sharing her unique perspective on how a donor’s gifts can be the beginning of something very special. To date, more than a million people have discovered her TED talk and four million have downloaded her Radiolab episode.

“I’m proud of my son because he has a job.”

She hopes more will learn about her experience and consider donating to research as an option. At a recent appearance at the Fountain Bookstore in Richmond, Sarah remarked about a woman who had experienced a similar loss and, having heard Sarah’s story on Radiolab, was inspired to also donate to research.

You can read more about Sarah Gray, her family and the impact of Thomas’ life and gifts, in her memoir, A Life Everlasting. The book is available for purchase from Amazon.